By Mohamed Oubihi* and Yasuhiro Ueno**

Biogen Idec, Senior Manager Japan and APAC Regulatory Advisor & EU Regulatory Development Regional Lead, Biogen Idec Ltd UK

** Clinical Trial Manager Japan, Biogen Idec Japan

Corresponding author: oubihi@gmail.com

Abstract

This article attempts to draw a comparison between the European Union and Japan on various aspects of clinical trials. This will include the overarching legal system that regulates clinical trials in both regions, a comparison of clinical trial infrastructure, the role of principal investigators and some of the operational aspects in running clinical trials in Japan and Europe. These issues will be approached from the perspective of their impact on global clinical development where Japan is now taking an active role. The article will briefly elaborate on the future and trends of clinical trial practice in Japan and Europe. There will be more emphasis on the differences especially on the Japanese side as many readers are probably much more familiar with the situation in EU.

1- Introduction

1- IntroductionSince 2007 MHLW has been encouraging foreign pharmaceutical companies to include Japan in their global clinical development plans in order to avoid delays in drug approval in Japan compared with the European Union (EU) and the united Sates (US) (1). Due to this change from the traditional bridging approach to simultaneous global clinical development, the number of global clinical trials performed in Japan has dramatically increased. The number of global clinical trial notifications (applications) filed in Japan has been steadily increasing by 25% from 2007 to 2009 (2) and is expected to keep growing over the coming years. The purpose of this article is to shed some light on the similarities and differences between the clinical trial practices and regulations in both regions and how they might impact global clinical development.

Drawing an accurate comparison between Japan and all member states in the European Union (EU) will not be an easy undertaking. There are several differences between national authorities within Europe in the implementation of the EU clinical trial Directive. The focus in this article will be on the aspects of clinical trials where member states in Europe are widely aligned.

2- The legal framework of Clinical Trials in Japan and EU

Europe has a Long history in establishing ethical and regulatory frameworks for the conduct of clinical trials but Japan has lagged behind in setting clinical trial standards. In Europe, the first national (legal or voluntary) codes for clinical trials were introduced in 1980s, but the first panEurope Directive 91/507/EEC which gave legal force to GCP in Europe was introduced in 1992. However, in Japan, The first framework for conducting clinical trials was not established until 1990 (what commonly referred in Japan as Old GCP). In 1996 Japan and EU signed ICH-GCP which was introduced in Japan in the form of GCP ordinance No. 28 in March 1997. The table below describes some of the key documents regulating clinical trials in both Europe and Japan.

Table 1: Main Regulatory Documents for the conduct of Clinical Trial in EU and Japan

| EU | Japan |

| Note for guidance on Good Clinical Practice July 1996 CPMP/ICH/135/95 | GCP ordinance No 28, 27th March 1997 |

| Clinical Trial Directive 2001/20/EC April 2001 | GCP ordinance No 106, 12th June 2003 |

| GMP Directive 2003/94/EC Oct 2003 | GCP ordinance No 172, 21st December 2004 |

| GCP Directive 2005/28/EC April 2005 | GCP ordinance No 72, 31st March 2006 |

| GCP ordinance No 24, 29th February 2008 |

3- Infrastructure of Clinical trials in Japan

Japan has a large network of hospitals and clinics, which are estimated according to an MHLW investigation to be respectively 8862 and 99532 sites (3). These institutions are spread all over the country but with high concentration in the Kanto area. However, until recently most of these trials were used to support approval in Japan rather than being part of global clinical trial. In a presentation by Tomas Salmonson from the Swedish Medical Product Agency only 15 investigational sites from Japan have contributed to MAAs submitted to EMA between 2005 and 2010. This is extremely low when compared with small countries like Israel (111 sites), or other emerging markets such as Argentina (150 sites) (4)

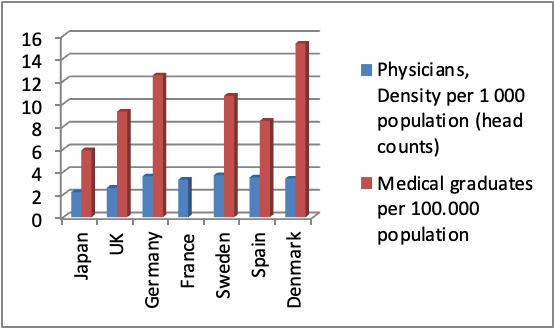

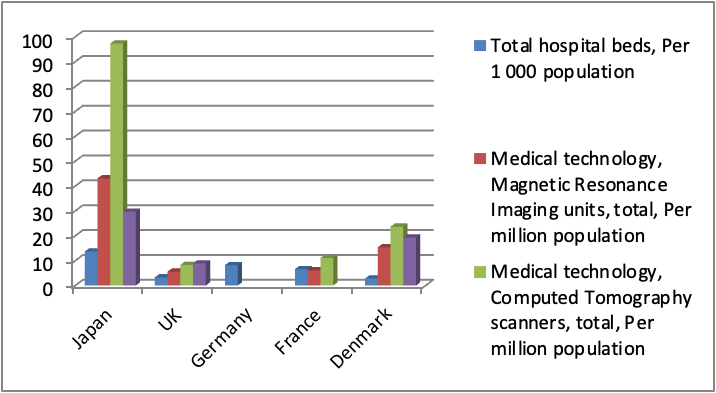

Physicians represent a key asset in conducting clinical trials. Compared to Europe, Japan has a relatively lower number of physicians per 1000 population. The number of medical graduates is also lower than major European countries such as UK and Germany (Fig 1). In addition, Japanese Doctors put in very long hours in hospitals dealing with patients consultation and have little or no time to spend on clinical trials. Fortunately this low number is being offset by the large number of Clinical Research Associates (CRA), and the increasing number in recent years of Clinical Research Coordinators (CRC) who play an instrumental role in supporting physicians and facilitating clinical trials. Japan has another unique entity that is called Site Management Organizations (SMO) which plays a pivotal role in supporting private hospitals and clinics to run clinical trials. On the other hand, the number of beds per hospital in Japan is almost two-fold that in European countries. In terms of advanced clinical equipment, Japan boasts an overwhelmingly high abundance of medical technology (CT scans, MRI and Mammographs) per population compared with other European countries as shown in Fig 2. (5)

As mentioned above, Investigators in Japan have less time but also less incentives compared with their Western counterparts to participate in Clinical Trials. The contracts are signed between the sponsor and the hospitals, not investigator; and the payment goes to the hospital administration with small fraction going to the investigator’s laboratory.

In Japan the amount of documentation required for IRB is relatively higher than what is required in Europe. This can be a logistic challenge as many Japanese sites have their own site contracts and templates, which increases the work load of Sponsors.

Fig 1: Japan has lower number of physicians per population than Europe

Fig 2: Hospitals in Japan are better equipped with advanced technology those in Europe

4- Scope of EU Clinical Trial Directive and Japanese GCP Ordinance

In Europe, the EU Clinical Trial Directive 2001/20/EC, and the GCP Directive 2005/28/EC, which are the key documents regulating clinical trials, cover all clinical trials excluding non-interventional trials. In 2006, the European Commission has also issued Draft guidance on ‘specific modalities’ for noncommercial clinical trials. In Japan, commercial-investigational clinical trials are governed by GCP ordinance, whilst commercial non-interventional clinical trials are not. Non-commercial-interventional clinical trials (e.g investigations initiated trials) are not under the scope of GCP ordinance unless the clinical trials data are planned to be used for new drug application.

5- Protection of Clinical Trial subjects

According to the EU Clinical Trial Directive, subjects should have a prior interview with the investigator to discuss the study and their rights before consent (In some European countries there is a need to wait 48 hours). In the Japanese GCP ordinance, a formal interview is not mandated, but there is a requirement that “the investigator should provide the subject with ample time and opportunity to inquire about detail of clinical trial and decide or not to enter the Trial”

6- Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board

Per EU Clinical Trial Directive, Ethics Committee on minors and incapacitated adults must have expertise or take advice from experts, but in Japan in this is not clearly specified in the GCP ordinance.

Regarding the timelines of the Ethics Committee (EC), in the EU there is a maximum of 60 days (30 days in gene therapy, somatic therapy and Genetic Modified Organisms) from date of receipt of a valid application to give its reasoned opinion. EC may send a single request for information supplementary to that already replied by applicant. However in Japan there is no limit to the number of requests from the Institutional Review board, and no set timeline.

7- Ethics and Regulatory Approval

In Europe, despite the differences between member states in implementing the Clinical Trial Directive, the regulatory and ethics approval pathways run in parallel. In Japan the regulatory approval by PMDA precedes the approval by the Investigational Review Board (IRB) at the study site. The regulatory approval process at PMDA is based on the principle of notification. PMDA approval is considered as being obtained if no negative response has been issued within the set timelines. Timelines at PMDA are 30 days for the first protocol for a new compound and 15 days for subsequent protocols with the same molecule thereafter. With the recent reforms in clinical trial infrastructure by the Japanese Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare, there are a few centers which have a centralized IRB system, but this is not widely used yet in Japan.

8- Regulatory Requirements

The core documents between EU and Japan are quite similar but the main difference is that PMDA do not require extensive CMC information in contrast to EU, except in the case of biotechnology/biological products, where a level of information, similar to that provided to EU regulators, is generally required. In addition, it is required to provide CRF with submission package in Japan which is not a requirement in most member states Europe.

Table 2: Core Regulatory Documentation for clinical trials in Japan and EU

| Japan | EU |

| Clinical Trial Notification Document | Clinical Trial Application Form |

| Scientific Rationale for the study | Protocol |

| Protoco | Investigational Brochure (IB) |

| Investigational Brochure (IB) | Investigational Medicinal Product Document (IMPD) |

| Informed Consent Form (ICF) | Manufacturer’s authorisation or Importer’s authorisation plus QP declaration on GMP for each manufacturing site. |

| Case Report Form (CRF) | Informed consent form |

| Examples of study drug labelling |

For global clinical studies, the protocol and CRF can be in English language. However, other key documentation, such as the IB and ICF, must be translated in the Japanese. Application forms and the scientific rationale for the study should always be provided in local language.

8- GMP Requirements

In Europe as well as in Japan, Investigational Medicinal Products (IMP) should be manufactured following GMP standards.

In Japan, GMP related documents are not required for Clinical Trial Applications. Only basic quality information is needed. PMDA trusts it is the sponsor’s responsibility to ensure IMP is GMP compliant. However, in EU, there is required to provide extensive data on quality attributes of IMP and GMP evidence.

9- Safety

The reporting periods of adverse events during clinical trials in EU and Japan are quite similar. For unexpected Fatal and life threatening events it is 7 days and for other serious events it is 15 days for both EU and Japan. The main difference is that Japan requires also the reporting of expected fatal and life threatening events within 15 days.

In Japan Periodic report for serious ADR is submitted to PMDA every 6months, while in Europe the Drug Safety Update Report is annual.

10- Paediatric Clinical Trials

In EU, there is a significant legislation on CT in Paediatric population. Besides the EU Regulation on Paediatric Medicines EC 1901/2006 issued on 12th Dec 2006, the EMA has also issued Ethical considerations for clinical trials on medicinal products in 2008. However, in Japan ICH E11 guidance (including Q&A on ICH E11 22nd June 2001) in addition to MHLW Notification 15th Dec 2000 are considered the only documents available on Paediatric Clinical Trials.

It is noteworthy to mention that in contrast to EU where paediatric investigational plan must be submitted to EMA early during the clinical development of a medicinal product, in Japan, clinical development in the paediatric population is not mandatory.

11- Comparator products

In both the EU and Japan, it is preferable that any active comparators in a clinical trial have at least one approval. For both Japan and the EU, more documentation is required to support use of an active comparator which is not approved in the region and central sourcing of such products is possible, but confirmation should be obtained from the supplier of their equivalence to the local source. For comparator products in Japan, it is normal to negotiate a “gentleman’s agreement” with the manufacturer of any active comparator product. This is not required by Japanese GCP, but is routinely done, and can add time to study start-up.

12- Impact of these differences on global clinical Trials

The challenges faced by global pharma companies involved in global clinical trials can be reduced to two main reasons: The cultural differences and the language.

The cultural differences:

The difference in the nature of business interaction and communication between sponsors, investigators and study sites in Japan compared with Europe, caused a lot of confusion in foreign companies and CROs navigating Japanese waters for the first time. The issues ranged from the tedious process of finalizing contracts with Japanese sites to the frequency of site visits and the required manpower. For instance, it was hard for foreign companies to accept making upfront payments instead of payment per milestone that is widely used in the West. Another challenge was the sheer number of visits CRAs need to make to study sites. While the site coverage by a CRA is about 3-4 sites in Japan, in Europe one CRA can handle up to 7 sites. Foreign companies couldn’t get to grips with the effort and time deployed for site initiation which often involves not only the CRO but also the local affiliate and large number of visits to the sites.

Limited English skills:

The other main challenge is English which is neither used in medical curricula nor in administration of hospitals and clinical trials.

In 2009 a survey was conducted on 50 pharmaceutical companies based in Japan on their experiences of global clinical trials (6). The main issue in implementing global clinical trials in Japan, was aversion to the use of English language (with 30% of respondents).

The other major Issue is the aversion of the principle investigator to use of English language in filling the CRF (73% of respondents). In more recent MHLW survey (2011) including 194 hospitals, with 52 of having global clinical trial experience, the top five issues encountered by these hospitals are related to the use of English (Comprehension of CRF in English, Filling in the CRF in English, Comprehension of protocol in English, and preparation of SAE in English)

13- Comparison of trends in Europe and Japan

In Europe some of the main trends in Clinical trials in Europe are very briefly highlighted below:

- Legislative proposal to revise Clinical Trials Directive 2001/20/EC in 2012: the purpose is to harmonize further the clinical trial legislation between member states in the EU.

- New EU Pharmacovigilance (PV) Legislation: The purpose is to have in place pro-active PV, to simplify regulatory decision making, to involving patients more closely in reporting ADRs, have greater transparency and to reduce administrative burden/increased work sharing

- Launching the EU Clinical Trials Register (https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/) which is the online register that gives for the first time public access to information on interventional clinical trials for medicines

In Japan MHLW has introduced major reforms to improve performance and global competitiveness of the clinical trial environment in Japan. The measures there have been major reforms in the clinical trial environment and regulatory policy

- In 2007 MHLW introduced a 5-Years Clinical Trial Activation Plan which includes the following measures:

1) Clinical Study Infrastructure Building,

2) Human Resource

Development for Clinical Research,

3) Public Promotion of Clinical Trial and Encouraging Participation,

4) Efficient Clinical Research Management and Sponsors’ Ease, and

5) Review GCP Ordinance and Clinical Research Guideline

- Promotion of Global Development and Clinical Trials

- Education of Staff involved in Clinical Research

- Public Promotion of Clinical Research (JAPIC, UMIN, and JMA CCT all one portal http://rctportal.niph.go.jp)

14- Conclusion:

In Both Japan and EU ICH-GCP lays the foundations of clinical research, both regions are very much aligned in terms of GCP principles, but sometimes practices tend to be different on how to achieve them. Whilst the EU is moving toward harmonization of its Clinical trials, Japan is improving its clinical trial infrastructure in order to encourage global clinical research

Acknowledgement:

The authors would like to thank Heather Taylor from Astra Zeneca for the critical review of the manuscript and for providing useful insights on the use of comparators in Japan

Disclaimer:

The information provided in these slides is based on the views of the authors and doesn’t reflect or represent in any way the position of Biogen Idec or any other party

References

1) Basic Principles on Global Clinical Trials Notification 0928010 Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare September 2007

2) PMDA data presented at Drug Information Association 4th Annual Conference for Asian New Drug Development Tokyo April 13-14

3) MHLW investigation report on hospitals and clinics 2007

http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/iryosd/07/kekka01.html

4) Tomas Salmonson Medical Product Agency: Importance of Asia in global development strategy presented at APEC Clinical Trial workshop in Tokyo Japan 1st Nov 2011

5) OECD Health 2008, 2009, and 2010

6) Pharma Stage Vol.8 No 10 2009 医薬品開発における国際共同治験の現状と問題点に関

する調査研究